At the time of opening, Brunel’s Box Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel ever built.

Controversial from the start, its problematic construction delayed the completion of the Great Western Railway’s London to Bristol route until June 1841. Today it is one of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s most celebrated structures.

An impossible project

Originally proposed in the Great Western Railway Act of 1835, building a tunnel through Box Hill was an impossible and dangerous engineering project according to its critics. Box Tunnel, located between Chippenham and Bath, was by far the most difficult single engineering work on the entire London to Bristol route as it contained the unusually steep gradient, by Brunel’s standards, of 1 in 100 over its length.

Bath Stone

Between 1836 and 1837 eight shafts were sunk at intervals through the hill and along the projected alignment to establish the nature of the underlying rock. Over the course of nearly two miles the tunnel dipped westbound through several overlying geological strata comprising of Great Oolite limestone (Bath Stone), and Inferior Oolite, Fuller’s Earth (which is particularly prominent in the Bath district) and a small amount of Lias Clay at the western end. At 9636ft (2,937m) with a 25ft (7.6m) diameter bore, contemporary reports put the total volume of material extracted from the tunnel at 247,000 cubic yards (189,000 cubic metres).

Two contractors were appointed to construct the tunnel; George Burge from Herne Bay was the major contractor, responsible for 75 per cent of the overall length of the tunnel working from the west, and Messers Lewis and Brewer, who were locally sourced contractors responsible for the remainder. Construction of the tunnel began in December 1838.

Railway navvies

Working conditions when building the tunnel were not good. Construction of the tunnel was divided into six isolated sections, and for much of the time access to these was only via the ventilation shafts, made 25ft (7.6m) in diameter, which ranged in depth from 70 to 300ft (21.3 to 91.5m). Blasting, which consumed 1 ton of explosives per week, took place within these chambers and with the workmen present. The only illumination was by means of candles, of which 1 ton weight was also consumed every week. During the early construction of the tunnel, workmen often had to evacuate as quickly as they could, as water gushed in from the Great Oolite strata. Pumping facilities had to be increased to deal with the considerable inflow.

The final piece

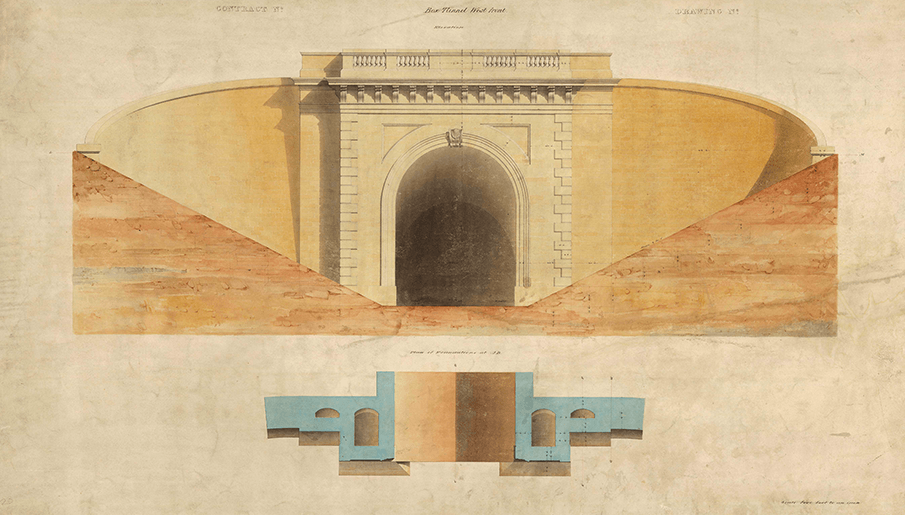

The overdue completion of Box Tunnel was delaying the opening of the whole line from London to Bristol as by August 1839 only 40 per cent of the tunnel had been constructed. By the summer of 1840 the Paddington to Faringdon Road (just east of Swindon) and Bath to Bristol sections of line had been completed. In January 1841, therefore, Brunel cajoled his major contractor to increase his workforce from twelve hundred to four thousand men, and by means of their superhuman effort the tunnel was effectively completed in April 1841. Work on the tunnel had begun from both the east and west sides of Box Hill in 1836; Brunel’s calculations, and the skills of the contractors and navvies were such that when the two ends met in 1841 the difference in their alignment was less than 2 inches (5cm). Brunel designed a grand classical portal for the west end of the tunnel but the east portal is less flamboyant with simple stonework. It opened to through London – Bristol traffic on 30 June 1841, without ceremony.

Did you know?

Legend has it that the rising sun shines through Box Tunnel on Brunel’s birthday, 9 April. Recent research has shown that unfortunately this is not the case, although the sun does shine directly through the tunnel on several other days throughout April and again in September.