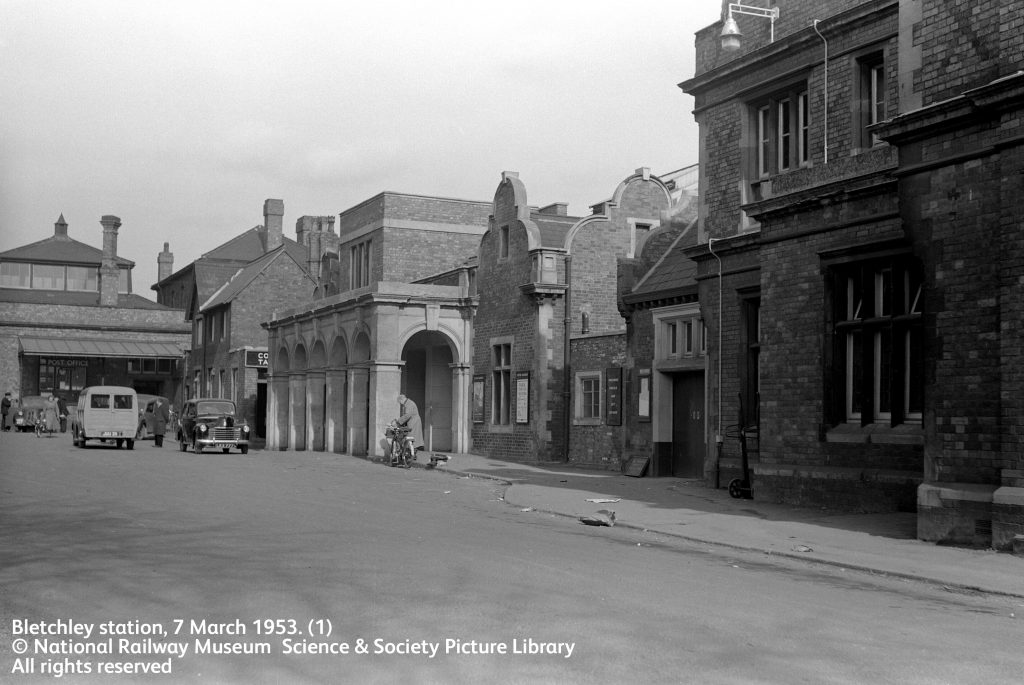

Sitting immediately south-east of a Victorian gothic country mansion in Buckinghamshire is arguably one of the most important railway stations of WWII.

For many young workers assigned to the Government’s ultra-secret cypher-breaking operation during the war, Bletchley railway station was the first glimpse of a world they could not speak about for decades.

“On arrival at Bletchley [station] you will find a telephone kiosk. Ring this number and await instructions,” was one of the orders for new recruits, who on reaching the park, instantly signed the Official Secrets Act, according to Voices of the Codebreakers: Personal Accounts of the Secret Heroes of World by Michael Paterson.

It said another was: “Take the exit from the arrival platform, go to the station forecourt and report to a hut on the far right hand side marked RTO (Railway Transport Officer) and show him but DO NOT GIVE him your envelope. He will direct you.”

The Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), a Foreign Office unit so secret barely anyone even at the highest levels of power knew it existed, moved into the former family home of Bletchley Park at the outbreak of war in 1939. It had stables, an old tennis court and a small lake, surrounded by acres of green fields.

It also had access to telecommunications cables that ran up nearby Watling Street, train services to London Euston and a convenient stop on the so-called Varsity Line linking Oxford and Cambridge, where GC&CS recruited mathematicians including computing pioneer Alan Turing.

Vital transport links

Tour guides at Bletchley Park often cite the rail links as one of the reasons the estate was chosen as the base for work that saved countless lives by reading secret messages – including those enciphered on Germany’s Enigma and Lorenz machines – and without which it is widely thought the war would have lasted beyond 1945.

Thomas Cheetham, a research officer at Bletchley Park Trust, said: “It wasn’t necessary for recruits to be able to arrive by train. However, the station was certainly convenient and was probably a factor in choosing the site.”

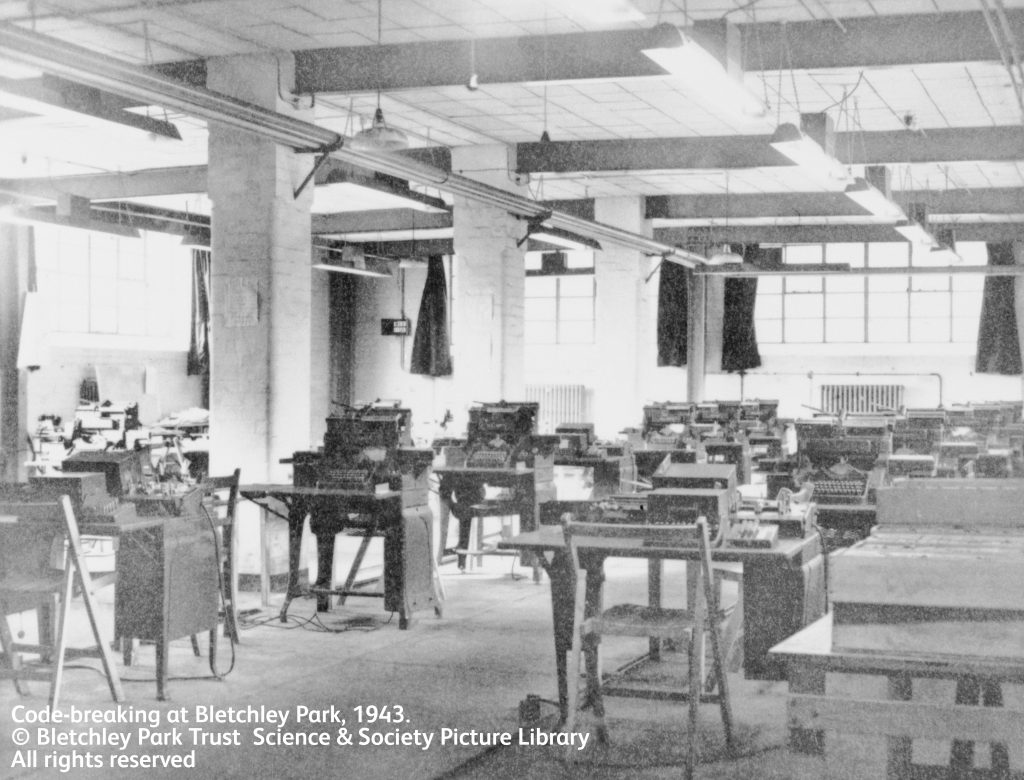

At its peak, more than 10,000 people worked at Bletchley Park and its wireless intercept stations, which supplied the encrypted messages.

Thomas said: “The railway was really important for the day-to-day commute of workers to BP… They were especially relied on by staff billeted in Wolverton, Bedford and Leighton Buzzard. In February 1944, there were 842 billeted in Wolverton, 308 in Bedford and 133 in Leighton Buzzard out of a total of 3,455 billeted civilians and 7,234 staff overall.”

Gallery: A Bletchley Park transport document dated 28 June 1944, showing BP’s efforts to get a larger workforce onto site just after D-Day. Images courtesy of Bletchley Park Trust.

D-Day

From March 1943, the railway was crucial in relieving the pressure on Bletchley Park’s own road transport services – GC&CS billeted staff in Bedford, thought to be the furthest commute at 18 miles from Bletchley.

An April 1944 memo said: “Until further notice, the majority of new civilian entrants will have to be accommodated in Bedford, until such time as they can be re-billeted in areas served by B/P Transport.”

Thomas said: “This was only possible because of the railway, and Bedford billets were initially reserved for day shift workers because they could commute by train.”

He added the memo probably related to staffing related to the preparations for D-Day on 6 June 1944. He said: “The staff had expanded somewhat prior to June to meet their [Operation] Overlord commitments and priorities agreed with the US Navy codebreakers… That seems to have caused some problems for the billeting office from about February onwards, forcing them to expand billeting in Bedford, and this seems to be the conclusion of the issue, once BP had been able to source enough coaches and drivers to put on a service for the Bedford shift workers when the trains weren’t running.”

Senior staff made frequent train journeys to London for meetings and to return to Oxford or Cambridge. In Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park’s Code-Breaking Computers by Jack Copeland, a Bletchley Park colleague sees Max Newman, famous for his work on the Lorenz cypher, at Bletchley station.

The colleague said: “He was dressed in a shabby old Burberry raincoat and was carrying a dead hare by the hind legs. He appeared to be searching the platform for something so I went up to ask if I could help. He gave me a distressed look and said that he had lost his ticket. We searched together but were unsuccessful, and as my train came in I tried to cheer him by saying I was sure the guard would believe him. His reply was: ‘Oh no, that is not my problem – until I find my ticket I cannot remember whether I am going to Oxford or Cambridge’.

Many of the ‘rank-and-file’ staff took leave in London and sometimes made it back for early shifts by hitching a lift on the early-morning ‘milk train’, according to Thomas.

Gwen Watkins of Air Section wrote in her book Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes: The Secrets of Bletchley Park: “Block F…was nearest to the private lane which led from the back of the Park to the railway station. If you slipped out of your section at five minutes to four (having brought in your weekend bag) and ran as fast as you could down the lane, you stood a good chance of catching the train from Birmingham which was supposed to arrive at three ten but nearly always ran late. Or you could stroll down in a leisurely fashion and catch the four ten to Euston, which nearly always came in before half-past four.”

Reinstating a lost line

GC&CS left Bletchley Park after the war and The General Post Office – with which Bletchley Park had close ties during WWII – took over the site as a training facility.

Bletchley station, now in Milton Keynes, remains a busy commuter terminus on the West Coast Main Line but the Varsity Line between Oxford and Cambridge closed in the late 1960s amid the recommendations of the Beeching Report of 1963 to save money by shutting railway lines.

Today, Network Rail is preparing to reinstate the line. The East West Rail project will re-establish a rail link between Cambridge and Oxford to improve connections between East Anglia and central, southern and western England.

In February, the project took a huge step forward when the Secretary of State for Transport approved our Transport and Works Act Order application for the first rail link in more than 50 years between Oxford, Bedford, Milton Keynes and Aylesbury. This approval has given us permission to start work on the next phase of the project.

The line will help to create jobs, boost economic growth, encourage people out of cars and onto public transport and enable sustainable development for generations.

Read more:

People and the railway: 75 years of Brief Encounter